After years of discreet negotiations mediated by Qatar, Oman and Switzerland, the U.S. and Iran have reportedly reached an agreement according to which Iran will release five imprisoned dual Iranian-American citizens in exchange for the U.S. release of five Iranians and Tehran gaining access to $6 billion of its frozen oil revenues.

While a win for diplomacy, this deal may prove to be a one-off rather than a prelude to more comprehensive talks between Washington and Tehran on other matters of discord, notably Iran’s nuclear progress, U.S. sanctions, regional security in the Persian Gulf, and Iran’s support for Russia’s war in Ukraine.

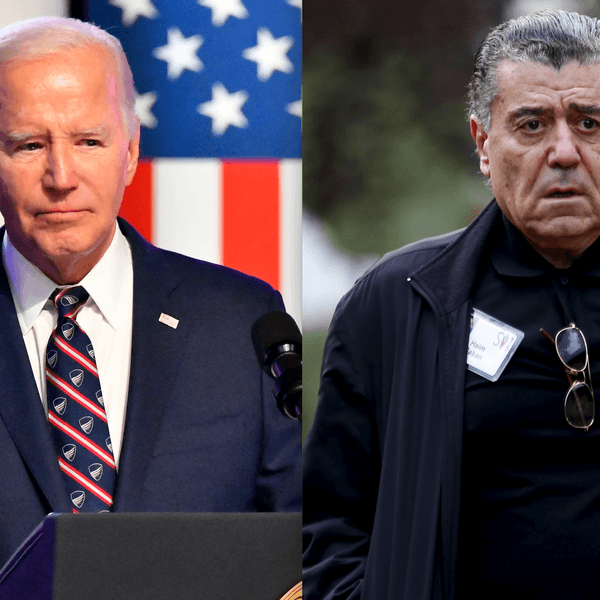

No sooner than the deal hit the news, it provoked the howls of outrage from the predictable quarters. The hawkish Foundation for Defense of Democracy (FDD)’s Mark Dubowitz denounced the Biden administration for giving the Iranian regime the money to “fund its war against Iranians, Americans, Ukrainians, Israelis and other innocents.”

FDD’s senior adviser Richard Goldberg, who served on Trump’s national security council while still being paid by FDD, deplored the deal as the “terrorism sanctions relief.”

Republican presidential hopeful and former Vice President Mike Pence also chimed in to attack Biden for paying “the largest ransom in American history to the mullahs in Tehran.” Exiled activist, Masih Alinejad, called on the U.S. to ask its allies to cut all diplomatic relations with Iran “until all innocent political prisoners are free.”

The outcry is clearly politically motivated, as it seeks to depict Biden as weak and soft on Iran. Yet on substance, the hawks’ objections to the deal are based either on ignorance or the deliberate distortions of facts.

To begin with, the $6 billion is not the money the U.S. is going to pay Iran to “buy” the prisoners’ freedom. These are Iranian assets in South Korea earned from the oil sales and frozen by Seoul under pressure by the Trump administration following its unilateral withdrawal from the nuclear agreement with Iran known as the JCPOA. This was followed by the introduction of unprecedented sanctions against Tehran, even though according to Trump White House officials Iran had been complying with its commitments under the 2015 deal.

Iran is essentially getting access to its own money which was withheld on no other legal basis than unilateral U.S. sanctions. And even that access is subject to a number of conditions.

According to the report in The New York Times, the funds in South Korea will be transferred to a bank account in Qatar under the control of its government — a close partner of the U.S. — to ensure that the funds can be used only to purchase humanitarian goods, such as medicine and food.

Iranians could justifiably view these limitations as infringing on their sovereign rights. Yet, the government is beset by economic hardship and rising public dissatisfaction and likely had no choice but to acquiesce to these terms.

Even the limited relief provided by this deal should still come as welcome news to the administration of Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi. Biden can also claim a win: the release of the unjustly imprisoned Americans at no actual cost to the U.S. Whatever the hawks’ vitriolic objections, granting Iran access to its own money and prisoners, in a strictly monitored and conditional way, cannot be seen as a major U.S. concession.

The broader lesson of this deal is that diplomacy still works: it is diplomacy that ultimately delivered the release of the Americans and hopefully will ensure their safe return home. If Biden had listened to the likes of FDD, Alinejad, and others who demand the perpetuation of Trump “maximum pressure” policy, the chances are that the suffering of the imprisoned Americans would be prolonged. Biden was right to ignore the hawks.

Unfortunately, however, the deal is unlikely to result in badly needed broader discussions between Washington and Tehran on their many differences, let alone a revived nuclear agreement. Biden’s priorities in the Middle East demonstrably do not include any kind of rapprochement with Iran.

Instead, he has thrown his weight behind the efforts to forge a deal between Israel and Saudi Arabia, following the blueprint of his predecessor-brokered Abraham Accords. In exchange for normalizing relations with Israel, the Saudis are demanding that Washington deliver a NATO-style commitment to their defense — presumably against their chief regional rival, Iran. Biden reportedly is considering it.

Iran, on the other hand, continues its nuclear advances and enhancing military cooperation with Russia, while pursuing its “look to the east” foreign policy. There are influential voices in Iran, such as the former foreign minister and head of Iran’s atomic organization (and some speculate a potential presidential candidate) Ali Akbar Salehi who call for comprehensive talks with Washington. And the elections to the Majles (the parliament) next year may yet see a comeback for the moderate and pragmatic forces due to Raisi’s deeply unpopular culture wars, including his stubborn insistence on enforcing mandatory veiling for women.

Yet any fundamental shifts from the current hardline ideological policies in the near future seem far-fetched.

The U.S.–Iran deal is a welcome and important development: if fully implemented, it will free the Iranian-Americans who should never have been imprisoned in the first place. It would also provide a much-needed economic relief for the Iranian people, at least in covering their basic needs. But the deal is likely to remain transactional rather than provide an opening for a broader dialogue between the U.S. and Iran, for which neither side currently appears to have much appetite.

![Following a largely preordained election, Vladimir Putin was sworn in last week for another six-year term as president of Russia. Putin’s victory has, of course, been met with accusations of fraud and political interference, factors that help explain his 87.3% vote share. If this continuation of Putin’s 24-year-long hold on power makes one thing clear, it’s that he and his regime will not be going anywhere for the foreseeable future. But, as his war in Ukraine continues with no clear end in sight, what is less clear is how Washington plans to deal with this reality. Experts say Washington needs to start projecting a long-term strategy toward Russia and its war in Ukraine, wielding its political leverage to apply pressure on Putin and push for more diplomacy aimed at ending the conflict. Only by looking beyond short-term solutions can Washington realistically move the needle in Ukraine. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, the U.S. has focused on getting aid to Ukraine to help it win back all of its pre-2014 territory, a goal complicated by Kyiv’s systemic shortages of munitions and manpower. But that response neglects a more strategic approach to the war, according to Andrew Weiss of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, who spoke in a recent panel hosted by Carnegie. “There is a vortex of emergency planning that people have been, unfortunately, sucked into for the better part of two years since the intelligence first arrived in the fall of 2021,” Weiss said. “And so the urgent crowds out the strategic.” Historian Stephen Kotkin, for his part, says preserving Ukraine’s sovereignty is critical. However, the apparent focus on regaining territory, pushed by the U.S., is misguided. “Wars are never about regaining territory. It's about the capacity to fight and the will to fight. And if Russia has the capacity to fight and Ukraine takes back territory, Russia won't stop fighting,” Kotkin said in a podcast on the Wall Street Journal. And it appears Russia does have the capacity. The number of troops and weapons at Russia’s disposal far exceeds Ukraine’s, and Russian leaders spend twice as much on defense as their Ukrainian counterparts. Ukraine will need a continuous supply of aid from the West to continue to match up to Russia. And while aid to Ukraine is important, Kotkin says, so is a clear plan for determining the preferred outcome of the war. The U.S. may be better served by using the significant political leverage it has over Russia to shape a long-term outcome in its favor. George Beebe of the Quincy Institute, which publishes Responsible Statecraft, says that Russia’s primary concerns and interests do not end with Ukraine. Moscow is fundamentally concerned about the NATO alliance and the threat it may pose to Russian internal stability. Negotiations and dialogue about the bounds and limits of NATO and Russia’s powers, therefore, are critical to the broader conflict. This is a process that is not possible without the U.S. and Europe. “That means by definition, we have some leverage,” Beebe says. To this point, Kotkin says the strength of the U.S. and its allies lies in their political influence — where they are much more powerful than Russia — rather than on the battlefield. Leveraging this influence will be a necessary tool in reaching an agreement that is favorable to the West’s interests, “one that protects the United States, protects its allies in Europe, that preserves an independent Ukraine, but also respects Russia's core security interests there.” In Kotkin’s view, this would mean pushing for an armistice that ends the fighting on the ground and preserves Ukrainian sovereignty, meaning not legally acknowledging Russia’s possession of the territory they have taken during the war. Then, negotiations can proceed. Beebe adds that a treaty on how conventional forces can be used in Europe will be important, one that establishes limits on where and how militaries can be deployed. “[Russia] need[s] some understanding with the West about what we're all going to agree to rule out in terms of interference in the other's domestic affairs,” Beebe said. Critical to these objectives is dialogue with Putin, which Beebe says Washington has not done enough to facilitate. U.S. officials have stated publicly that they do not plan to meet with Putin. The U.S. rejected Putin’s most statements of his willingness to negotiate, which he expressed in an interview with Tucker Carlson in February, citing skepticism that Putin has any genuine intentions of ending the war. “Despite Mr. Putin’s words, we have seen no actions to indicate he is interested in ending this war. If he was, he would pull back his forces and stop his ceaseless attacks on Ukraine,” a spokesperson for the White House’s National Security Council said in response. But neither side has been open to serious communication. Biden and Putin haven’t met to engage in meaningful talks about the war since it began, their last meeting taking place before the war began in the summer of 2021 in Geneva. Weiss says the U.S. should make it clear that those lines of communication are open. “Any strategy that involves diplomatic outreach also has to be sort of undergirded by serious resolve and a sense that we're not we're not going anywhere,” Weiss said. An end to the war will be critical to long-term global stability. Russia will remain a significant player on the world stage, Beebe explains, considering it is the world’s largest nuclear power and a leading energy producer. It is therefore ultimately in the U.S. and Europe’s interests to reach a relationship “that combines competitive and cooperative elements, and where we find a way to manage our differences and make sure that they don't spiral into very dangerous military confrontation,” he says. As two major global superpowers, the U.S. and Russia need to find a way to share the world. Only genuine, long-term planning can ensure that Washington will be able to shape that future in its best interests.](https://responsiblestatecraft.org/media-library/following-a-largely-preordained-election-vladimir-putin-was-sworn-in-last-week-for-another-six-year-term-as-president-of-russia.jpg?id=34283894&width=1245&height=700&quality=90&coordinates=0%2C77%2C0%2C77)