It was the end of the 1980s and the Guardian’s Middle East correspondent, Ian Black, was talking shop with his competitor at the Sunday Times, the late Marie Colvin. “We were discussing when there might be a Palestinian state,” Black recalls of their conversation in Jerusalem. “We thought maybe it would happen in two or three years.”

Israel and the Palestinian territories were deep into the first intifada, an uprising against the occupation that lasted from 1987 until the early 90s. It was a period in which violence spiked, but also a time of nascent hope that the lengthy military grip over Palestinian life might finally end.

Some believe it almost did when the Oslo accords, a series of steps intended to fulfil the right of Palestinians to determine their own fate, were signed in 1993.

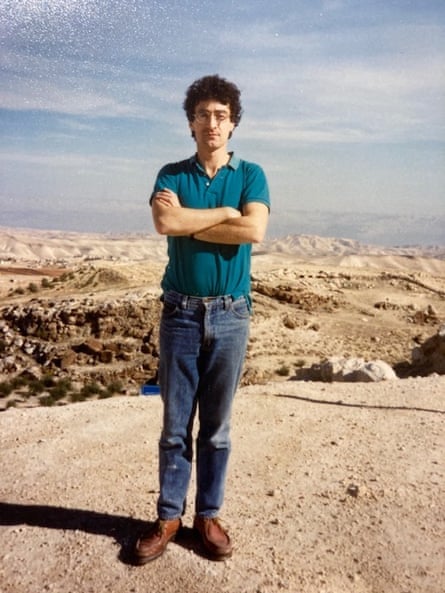

Black left Jerusalem shortly before that hugely newsworthy event with what he jokingly laments was “impeccable timing”. Still, even when he was reporting in the years before that, “the direction of travel”, he says, was fairly clearly towards some attempt at a resolution.

Today, that hope has all but vanished. In the three years I have spent as the Guardian’s Jerusalem correspondent, I cannot remember a single conversation with another reporter in which a Palestinian state was considered a likely near-future scenario.

Three decades have separated Black’s assignment from mine. In that time, the Oslo accords have been derailed by the assassination of an Israeli prime minister by a far-right zealot, a much-bloodier second intifada has left the peace process in ruins and the occupation has become entrenched.

Now there is widespread talk in Israel about making its military hold over Palestinians a permanent one. Several anti-occupation Israeli and Palestinian voices claim it already is. They argue that the 90s-era ideal of two states side by side is becoming an impossibility, and a single, undivided and unequal Israeli state has emerged.

“You have spent the past three and half years reporting on a one-state reality, whereas I spent my years with the underlying assumption that a two-state solution was possible,” said Black, 67. “And that’s gone.”

As my colleagues at the Guardian talk to their predecessors for the paper’s 200th anniversary, there will undoubtedly be similarly large differences in their beats. But in many ways, on a smaller scale, Black’s daily life mirrored my own.

He would buy morning newspapers in the shop while I can read them online. He would travel, to the West Bank or Gaza, along the same roads I use. He even attended briefings with some of the same people.

This is particularly noticeable on the Palestinian side, whose ageing leadership has largely refused to hand the spotlight to a younger generation. In 1991, Black profiled Hanan Ashrawi, calling her “the most famous spokesperson her people had ever had”. Ashrawi only retired in December, saying the Palestinian political system needed “renewal and reinvigoration” to include youth and women.

What has changed is the scale and effectiveness of the occupation we have reported on. Looking over his old clippings, Black said he saw an article he wrote from the mid-80s. “I was astonished to find there were only 30,000 settlers.”

Roughly 600,000 Israeli Jewish settlers now live in the West Bank and east Jerusalem with no intention of leaving, connected through a network of government-maintained highways. Palestinians remain largely confined to urban enclaves.

Was this outcome predictable during Black’s time, when there was so much hope of a resolution? One criticism made of the Guardian is that it has focused too much on voices in Israeli society calling for an end to the occupation, having the effect of perhaps misleadingly magnifying their domestic influence. Readers have been left wondering how Israeli politics has since lurched so far to the right.

“I think in the big picture, the Guardian indulged – including the correspondents and including me – in wishful thinking. I really do,” said Black. But he explains: “Israeli society was more divided then, 30 or so years ago, than it is now.” The turning point, he says, was the second intifada, which decimated any trust between Israelis and Palestinians.

Black has left Jerusalem but remains deeply engaged. Since leaving the paper, he became a visiting senior fellow at the Middle East centre at the London School of Economics. His book, Enemies and Neighbours: Arabs and Jews in Palestine and Israel, 1917-2017, has become a go-to account. I keep a copy in my office.